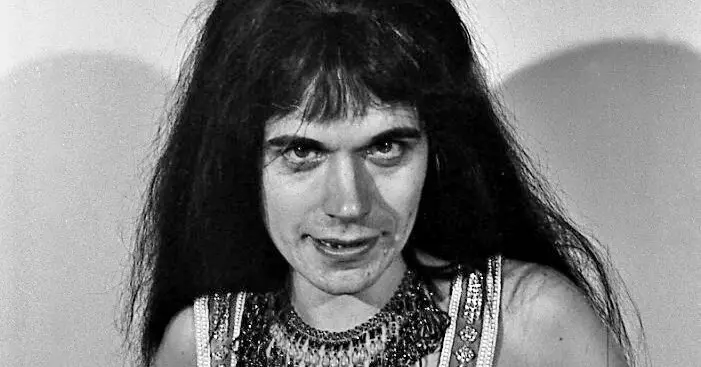

Rumi Missabu, an avant-garde drag performer who was best known as a member of the anarchic, glitter-encrusted, hippie-drag troupe known as the Cockettes, which bloomed briefly at the turn of the 1970s in San Francisco, died on April 2 at his home in Oakland, Calif. He was 76.

His death, from complications of chronic respiratory disease, was announced by Griffin Cloudwalker, a friend.

For a moment, the Cockettes were the bohemian darlings of San Francisco. Their members were a diverse collective that included Rumi, a voluble drama student from Los Angeles. Like many in the group, he went by his adopted first name only. And like so many in the late 1960s, he had fetched up in the Haight-Ashbury district, drawn there by the alluring swirl of spiritual questing, political activism, experimental theater, free love and psychedelics.

The Cockettes lived communally in the derelict Victorian houses there and devoted themselves to self-expression. Their bodies were their canvases, which they bedecked in feather boas, tutus, corsets, Victorian petticoats, Edwardian frock coats, wigs, wings, headdresses, ribbons, sequins, rhinestones, satin, face paint and an abundance of glitter.

Their leader was a young actor named George Harris III who had made his way from New York City to San Francisco in 1967, the same year he was famously captured by the photojournalist Bernie Boston at an antiwar protest, tucking flowers into the barrels of the rifles held by the military police. In San Francisco, he transformed into Hibiscus, a show-tune-loving mystic with flowing hair and a glitter-coated beard — “like Jesus with lipstick” is how one Cockette described him. He gathered his friends first into street theater, then onto the stage of the Palace Theater in North Beach, where the Cockettes made their debut on New Year’s Eve in 1969.

They named themselves just before that show, as a spoof of — and perhaps in homage to — the high-kicking Rockettes, and poured out onto the stage that night in a chaotic, campy cancan that ended in a joyful nude scrum, with the audience joining them onstage to the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women.”

They became regulars at the Palace, appearing monthly, and began, sort of, to plan their shows: In “Gone With the Showboat to Oklahoma,” Rumi played Belle Watling, the madam from “Gone With the Wind”; “Pearls Over Shanghai” was about three girls kidnapped by a brothel owner named Madame Gin Sling, again played by Rumi.

“It was extremely experimental theater,” Fayette Hauser, an artist and photographer who was one of the few female Cockettes — and whose visual memoir, “The Cockettes: Acid Drag & Sexual Anarchy, 1969-1972,” was published in 2020 — said by phone. “We had themes. There were no scripts. No rehearsals. Everyone was very individuated, and we expressed ourselves in drag. High drag, we called it.

“Rumi, in particular, had a complete and glorious sense of self, which I admired,” she added. “He knew who he was and wanted to put it out there. It helped that he had trained as an actor, unlike most of us.”

He also performed, invariably and reliably, on acid, though not every Cockette was tripping onstage, Ms. Hauser said — herself included, because LSD made her nonverbal.

By 1971, the Cockettes were stars of the underground press and attracted audiences beyond their counterculture peers. One Friday in September, Rex Reed, the syndicated New York-based arts critic, brought Truman Capote; Johnny Carson’s former wife, Joanna Carson; and a few San Francisco socialites to see a show that night called “Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma.”

Writing about it the next week, Mr. Reed summed up the evening as “a nocturnal happening comprising equal parts of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street, Harold Prince’s ‘Follies,’ and movie musicals, the United Fruit Company, Kabuki and the Yale varsity show, with a lot of angel dust thrown in to keep the audience good and stoned.”

The filmmaker John Waters, interviewed in “The Cockettes,” a 2002 documentary directed by David Weissman and Bill Weber, said their shows were “complete sexual anarchy, which is always a wonderful thing.”

The first Cockettes performance consisted of just 10 men, three women and a baby. Rumi, who decades later appointed himself the archivist of the group, estimated that in later productions the cast stretched to more than 100 people — including Sylvester, who would go on to enjoy success as a disco singer, and, for a few performances before the group split up in 1972, Divine, Mr. Waters’s longtime muse. Many of the Cockettes, including Rumi, appeared in “Elevator Girls in Bondage” (1972), an underground film about a staff revolt in a seedy hotel.

As early as 1971, however, the group was splintering into factions: those who wanted to make the shows more professional and those, like Hibiscus and Rumi, who wanted to keep to their improvisational and free-ethos origins. When the Cockettes were invited to perform in New York in the fall of 1971, Hibiscus and Rumi opted out. Poignantly, the Cockettesbombed there.

“This is a drag show to end all drag shows,” Mel Gussow of The New York Times wrote in his review, “the kind of exhibition that murders camp.”

Rumi, meanwhile, had joined a group of like-minded performers, convened by Hibiscus and called the Angels of Light, who staged happenings in the Bay Area before bringing them to New York City theaters, including the Theater for the New City, in the early 1970s. Hibiscus died of AIDS in 1982.

Rumi careened in and out of the Angels of Light, and in and out of New York, before making his way back to San Francisco later in the decade And then he more or less disappeared, working cash jobs as a house cleaner and occasional caterer. He had no bank account and no government identification, save for an old library card.

When a group of Cockettes held a 25th-anniversary reunion in 1994, he resurfaced. For the next three decades, he performed on his own and in revivals of the Cockettes’ shows and became a mentor to young gay performers.

“I came in out of the cold,” he told Daniel Nicoletta, a photographer, who began documenting his shows.

Rumi was born James Allen Bartlett on Nov. 14, 1947, in Los Angeles, the eldest child and only son of Ruth Irene (Brown) Bartlett and Earl Oliver Bartlett, an auto mechanic and gas station owner.

He began acting in high school and studied drama at Los Angeles City College, living with his high school friend and theater pal Cindy Williams, who supported the two of them by working as a waitress. (Ms. Williams would go on to co-star with Penny Marshall in the long-running sitcom “Laverne & Shirley.”)

On acid one night, Rumi saw a low-budget exploitation horror film, “She Freak,” which sparked something in him. He took a Greyhound to San Francisco, moved into an empty water tower with three roommates and tumbled right into the Haight scene. He christened himself Rumi, for the 13th-century Sufi poet and counterculture favorite. His adopted surname came later, although friends don’t remember when, or what inspired it.

Rumi is survived by his sisters, Mary Bartlett Dobyns and Debbie Mitzlaff. In 2015, he began donating his archive to The New York Public Library.

Rumi performed until he couldn’t, flying to New York, oxygen tanks in tow, to stage productions at venues like Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. The performances were elaborate and demented, always free and for one night only. His last show, at Judson in October 2019, was a Kabuki extravaganza called “Demon Pond,” adapted from a Japanese play of the same name. Rumi did not perform, but he directed and narrated the play, which involved, among other things, a lovesick dragon and an apocalyptic flood.

“The show was about tenacity and redemption,” said Mr. Cloudwalker, his friend, “and it was a great swan song.”