In the early years of the Cold War, with the Space Race heating up, weapons testing ongoing and proxy conflicts raging around the world, the United States Army decided it needed to take a decisive step for national security. The plan? Conquer the Moon. Or at the very least establish a forward operating base on the lunar surface.

This was a very real plan considered by the Army. In fact, the Army wanted a nuclear-powered intelligence base on the lunar surface in the middle of the 1960s, staffed by 12 soldiers who would be armed with several types of space weapons, including guns derived from claymores. ‘Project Horizon, A U.S. Army Study for the Establishment of a Lunar Military Outpost’ was a 1959 study by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency looking into this very real proposal that the military was considering.

“I envision expeditious development o! the proposal to establish a lunar outpost to be of critical importance to the U.S. Army of the future,” Lt. Gen. Arthur Trudeau wrote in the introduction to the paper.

This wasn’t that out there for the U.S. military at the time. This is the late 1950s. This is at a time where, post-Sputnik and in the depth of the Cold War arms wars, the U.S. was looking at any idea, no matter how seemingly out there it was. The Pentagon looked at nuclear air-to-air missiles, shoulder-fired nuclear weapons, even a plan to detonate nukes to create essentially a death cloud that could blanket the Soviet Union. With the space race only just beginning, maybe a lunar landing and an eventual lunar base wasn’t out of the question.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

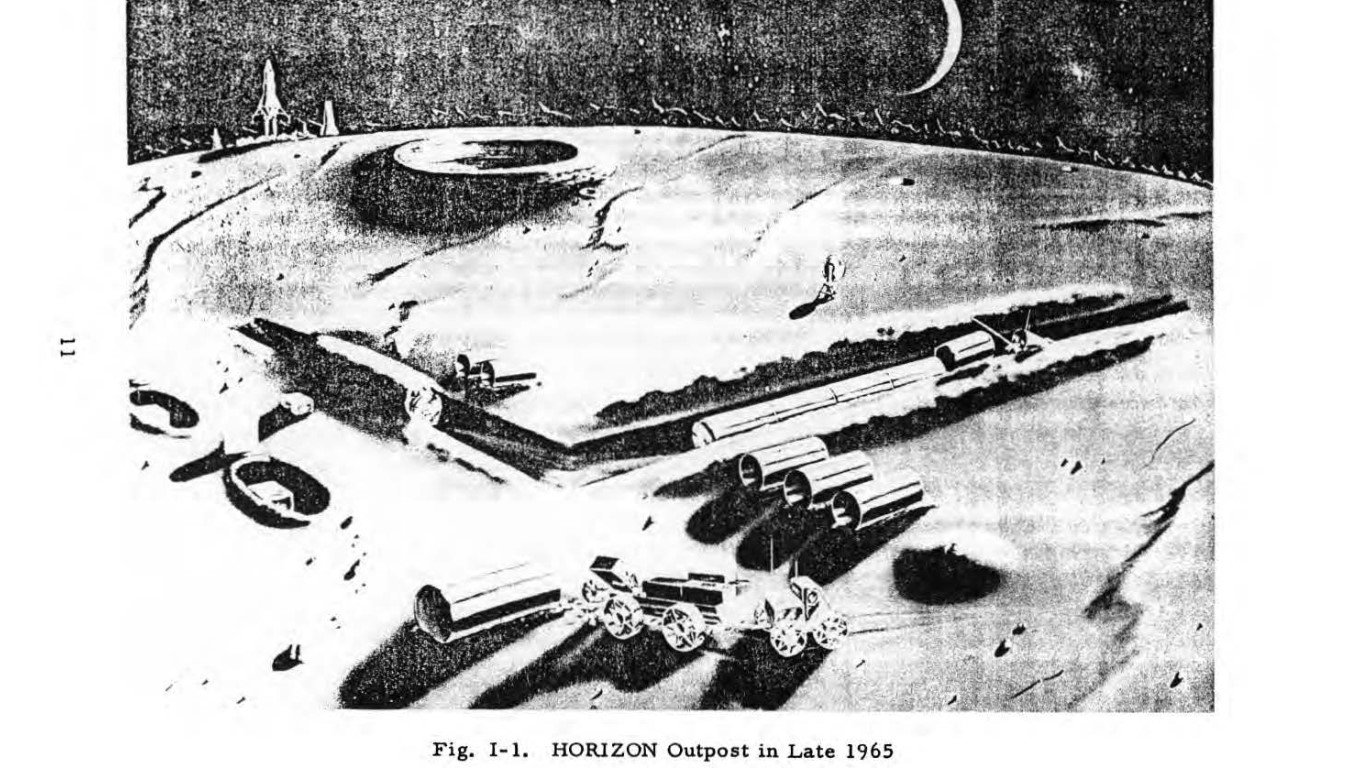

Project Horizon called for several major steps to establish the lunar outpost. Utilizing ongoing development of the Saturn I and II rocket systems, the Army would start launching cargo and a pair of soldiers in 1965, who would begin constructing the Horizon base. Another 149 launches would bring cargo to the base, until it was fully staffed with 12 crewmembers by November 1966. The next year would see 64 more rockets arrive, as the Army carried out the first year of lunar operations. As for the potential base, the Army’s paper lays out the initial requirements. The first portion of the outpost would need to be designed to be sustainable, able to house personnel (between 10-20 people) for a prolonged time and be built so that additional components can be constructed as it grows. The base itself would be a series of tubes, and powered by nuclear reactors.

Also the soldiers would be armed. Even though Project Horizon was mainly planned as an intelligence gathering and communications outpost, it was still intended to be a military site. As such, soldiers would be armed with several types of weapons, developed for space. Those ranged from rifles derived from claymores to modified pistols. Notably, these are more primitive and bulky than the weapons the Army would propose for lunar warfare six years later. The Army even outlined potential space suits, but correctly noted they would be cumbersome and would make it difficult to operate weapons. Of course, if Project Horizon had worked, there was a fair chance the base would have pretty early warning of any hostile force approaching from Earth.

Keep in mind, much of Project Horizon was speculative. The study was done in 1959, two years before Yuri Gagarin became the first human in orbit and six years before cosmonaut Alexei Leonov became the first person to do a space walk. The Saturn rockets called on for hauling the construction equipment for the lunar base were still in development, and much of the 1960s would be spent on careful testing of space technology in the Mercury and Gemini programs. However, the Army found that given the “explosive” rate of rocket development, the proposal for establishing the base in 1965 was “realistic.”

The Army wasn’t alone in this research — prior to the creation of NASA the different military branches were pursuing their own plans for space exploration and launches. In April 1960, the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division published its own paper, ‘Military Lunar Base Program, or, S.R. 183 Lunar Observatory Study.’ The paper looked into the possibility of establishing a lunar intelligence base, and said that such an idea is not for the “far off future” but one that should be done “immediately.” Interestingly, the paper’s predictions aren’t too far off from reality; the Air Force suggested that someone could land on the Moon in 1967, just two years before it actually happened.

Unfortunately for the thinkers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as well as fans of speculative fiction, there is no lunar base, nor military outposts on the Moon. Project Horizon was felled, not by technological challenges or military conflicts, but the price. At an estimated cost $6 billion at the time, President Dwight D. Eisenhower decided that Project Horizon was too expensive to pursue. His successor John F. Kennedy, although an advocate for space exploration, didn’t seek to revive it. Meanwhile, NASA took over as the lead agency on space research and development. So Project Horizon remains a “what if” and the source of some fascinating conceptual art.