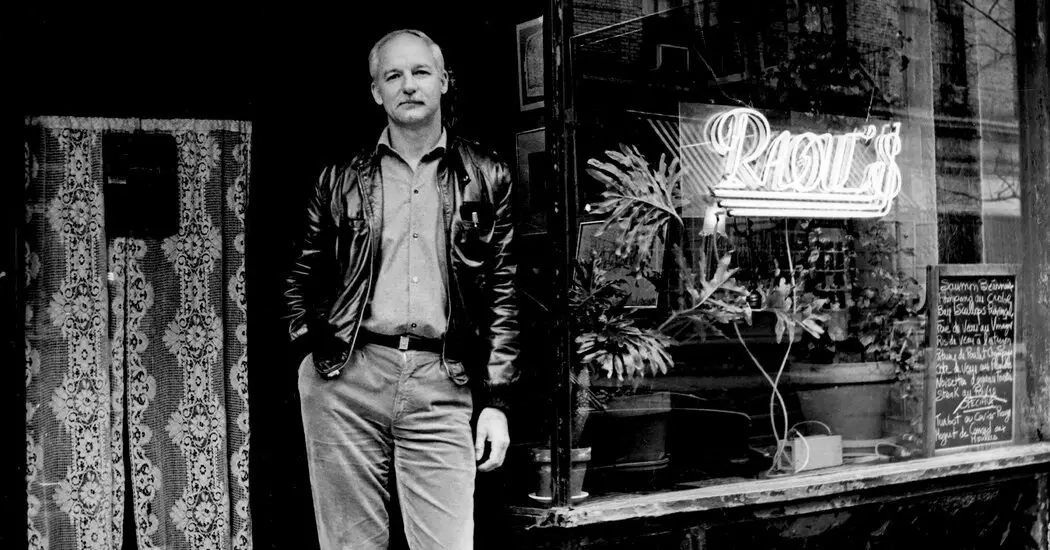

Serge Raoul, an Alsatian-born former filmmaker who with his brother, Guy, a classically trained chef, founded Raoul’s, a clubby French bistro and SoHo canteen in Lower Manhattan that drew generations of artists, rock stars, writers, models, machers and movie people — along with those who yearned to be near them — died on March 8 at his home in Nyack, N.Y. He was 86.

The cause was a glioblastoma, said his son, Karim Raoul.

Raoul’s opened in 1975 — it’s still operating under his son’s watch — when the SoHo neighborhood was a partial wasteland, peopled by the artists who had been slowly colonizing the derelict former warehouses there and the thriving Italian community in the tenements to the west.

Serge was on hiatus from making documentaries and Guy had been working as a chef uptown when Serge set out to find him a restaurant. A friend thought Luizzi’s, a cozy and well-worn spaghetti-and-meatballs joint on Prince Street between Sullivan and Thompson, might be for sale. As it turned out, the owners, Ida and Tom Luizzi, were happy to make a deal if it included the provisions that Mr. Luizzi could drop in every day and that Inky the cat could stay.

As for the battered décor, the Raoul brothers ejected the Chianti bottles on the tables, but they kept the rest: the bar, the booths, the tin ceilings and walls, and the fish tank at the back. (They would replenish it over the years with generations of goldfish.) The fridges and freezers were still full of Italian fare, and for the first two weeks, until the food ran out, Raoul’s menu was mostly Italian.

“We had no money, so we kept it the same,” Guy Raoul said.

Mr. Luizzi appeared each morning to open the place, then stayed in the kitchen with Guy while Serge ran the front of the house.

The first customers were neighborhood artists, like James Rosenquist and David Salle, and the gallerists who had followed them downtown, along with Serge’s colleagues from French TV, where he had worked for a decade.

Some locals paid their tabs with artwork, and the restaurant’s walls began to fill. The Raouls added their own touches, including a portrait of Charles de Gaulle. Inky was a louche accessory, draping himself along the backs of the banquettes, except during Health Department inspections, when he was banished to the basement. There were some minor cash infusions, like the $500 an Israeli friend paid to shoot a porn movie there. The restaurant limped along, and then began to sprint.

“Everybody comes to Raoul’s,” Seymour Britchky wrote in a review for New York magazine in 1980. “Prosperous painters and starving art dealers, garishly garbed locals and uptownies in jackets that match their pants — the rich and the ragged. Raoul’s is democracy at work at play.”

“It’s got my enemies and friends — and my type of food,” Robert Hughes, the Australian art critic, told Peter Foges, then the BBC’s New York bureau chief, when Mr. Hughes brought him to Raoul’s in the early 1980s. (Mr. Hughes ordered the steak au poivre, the house dish.)

Mr. Foges remembered seeing Julian Schnabel and Mr. Salle at the bar, joined by the gallerist Mary Boone, who, as he wrote in an essay in 2018, shot Mr. Hughes “a look of pure hate as she passed.” Mr. Foges was entranced by that first visit and often returned with Christopher Hitchens, the caustic writer, staying long enough to close the place. (The early cast of “Saturday Night Live” often closed the place, too, mugging for one another in a booth; John Belushi lived on nearby Morton Street.)

One night, on his way out, Mr. Foges encountered Andy Warhol who took a Polaroid photo of him, pocketed it and, as he wrote, “swept off in a large limousine.”

The go-go ’80s lifted the art market and Wall Street, and the rising fortunes of both lifted Raoul’s.

Serge Raoul, courtly and reserved, was a reluctant front-of-the-house man. And he liked to duck out every once in a while to work on a film. So he needed a proxy. He had a talent for hiring, which he did by instinct, and he let his staff have their heads. Philip Saunders, one of the waiters, brought in Rob Jones, a sculptor with a flair for the theatrical, and Serge hired him on the spot as maître d’hôtel.

The charismatic Mr. Jones was a natural in the role, and then some. One night soon after he began working there, as the dinner service was winding down, Mr. Jones was moved to metamorphose into a drag version of Dusty Springfield, the English pop star. Clad in a pink cloth coat, a blond wig and a feather boa, Mr. Jones’s Dusty made her entrance down the precarious spiral staircase that led to the bathrooms upstairs, lip-syncing Ms. Springfield’s hits “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me” and “Wishin’ and Hopin.’”

The act became a Raoul’s staple, as did its preamble, during which diners chanted “Dusty, Dusty” to coax Mr. Jones, faux-bashful, to get in character. To set the scene, Eddie Hudson, a bartender, would blast the steam valves on the two espresso machines and dim the lights. Mr. Jones was sometimes moved to extend his act onto the bar, and he was often joined by waiters, with Mr. Hudson spotting from behind. Nobody got hurt, but one year Mr. Jones kicked the fish tank over.

“Rob was one of our greatest assets,” Guy Raoul said.

It was Mr. Jones who conspired with the photographer Martin Schreiber to hint that one of Raoul’s most notorious artworks, the enormous portrait by Mr. Schreiber of a languorous nude redhead reclining on a green velvet couch, was in fact Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York. It was not, but the ruse added a bit of royal luster. Not that the place needed it.

Mr. Jones performed for the last time on New Year’s Eve in 1988. He had retired Dusty a few months earlier, but she made her comeback that evening. Mr. Jones died of AIDS three weeks later.

As for the cuisine, it was never the plan to turn the place into a Lutèce, the Upper East Side temple to haute French cuisine. The idea, Guy said, was to bring some French flavor downtown. The menu was classic bistro fare: artichokes vinaigrette, pâté maison, steak au poivre. “Whoever would go there would not be overwhelmed,” Guy said. “There would be no intimidation with the food. If you wanted to eat with your fingers, that was OK.”

Serge Raoul was born on Oct. 9, 1937, in Altkirch, a town in France’s eastern region of Alsace. His parents, Hélène (Scherrer) and Joseph Raoul, ran a restaurant opened by Joseph’s father that catered to factory workers at the local cement plant.

Serge had no intention of joining the family business, however, and trained, randomly, to be an electrician. His parents divorced at the end of World War II, and his mother moved to Paris. Serge joined her there when he was 18 and went to work for French radio as a sound technician.

By 1962 he was working for the United Nations, living first in New York City and then Congo, where he helped set up a U.N. radio station. After a decade as a New York-based correspondent for French TV, he spent six months in Kenya making a documentary about the Masai.

Meanwhile, Guy, 13 years his junior, had been training to be a chef. When Serge returned to New York on sick leave, having contracted malaria, he began to hunt for a restaurant for himself and his brother. He thought he might run it for a bit, and then return full time to filmmaking. But he found himself hooked.

In addition to his son and brother, Mr. Raoul is survived by two granddaughters. His marriage to Priscilla Zavala ended in divorce in the mid-1980s, after the couple had moved to Nyack. For a time, there was a Raoul’s in that Hudson River town and another in Bali.

In 1986, Mr. Raoul opened a new Lower Manhattan restaurant on Varick Street with Thomas Keller, then a young chef, whom he hired for a moment in 1981 before sending him off to Paris to train. They named it Rakel’s — a portmanteau of both men’s last names — and it became a showcase for Mr. Keller’s esoteric and ambitious cuisine. When the recession hit in 1990, Mr. Raoul revamped the place, and Mr. Keller left; Mr. Raoul oversaw a few more iterations of the restaurant before shutting it down a few years later.

“He transformed the trajectory of my life and made me the chef I am today,” Mr. Keller wrote on Instagram after Mr. Raoul’s death.

Mr. Raoul retired in 2014, after having a stroke, and his son took his place.

Raoul’s turns 50 next year. On a recent night, patrons were three deep at the bar, and there wasn’t a reservation to be had.