In June 2017 — as he was reeling from the end of his marriage of more than two decades and some of the most disastrous investments of his career — Bill Ackman, the billionaire hedge-fund financier, joined Twitter.

In his few posts that year and the next, Mr. Ackman, now 57, shared a picture of himself posing in line at the fast-food chain Chipotle, one of his largest investments; links to position papers on another investment, ADP; and a news release announcing the winners of his foundation’s awards. He offered his early Twitter followers little of the drama that was part of his investing style and would later become a hallmark of his round-the-clock social media posts.

Just a few months later, Mr. Ackman went on his first date with a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor, Neri Oxman. He was instantly smitten, and asked her on that date if she was open to having children, he told the crowd last year at an awards dinner.

By 2018, at his annual investor meeting for his hedge fund Pershing Square, he told investors he was certain his firm’s performance, which had been suffering, would turn around because he was in love with Dr. Oxman. They married the following year.

And yet, it was arguably the other new relationship in his life that helped him past his professional rut: Twitter.

Mr. Ackman has credited his use of the platform with helping him see around corners during the pandemic. His $27 million bet against the market became $2.7 billion in a matter of weeks in early March 2020. (Forbes calculates his net worth at $4.3 billion.)

In the years since, Mr. Ackman’s use of Twitter, now X, has pushed him into the realm of celebrity far beyond the investment world. He has more than 1.2 million followers on the platform, where he and X’s owner, Elon Musk, frequently amplify each other.

Only a few other titans of finance have more than 100,000 followers. His longtime nemesis, the hedge fund manager Carl Icahn, has 464,400 followers. Ray Dalio, the founder of the hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, has eclipsed Mr. Ackman with 1.3 million.

Thanks to the platform, his fans are now an unlikely nexus of people: everyone from right-wing zealots fighting any push for diversity to liberals worried about antisemitism. Even Mr. Icahn said he agrees with some of what Mr. Ackman has been posting about.

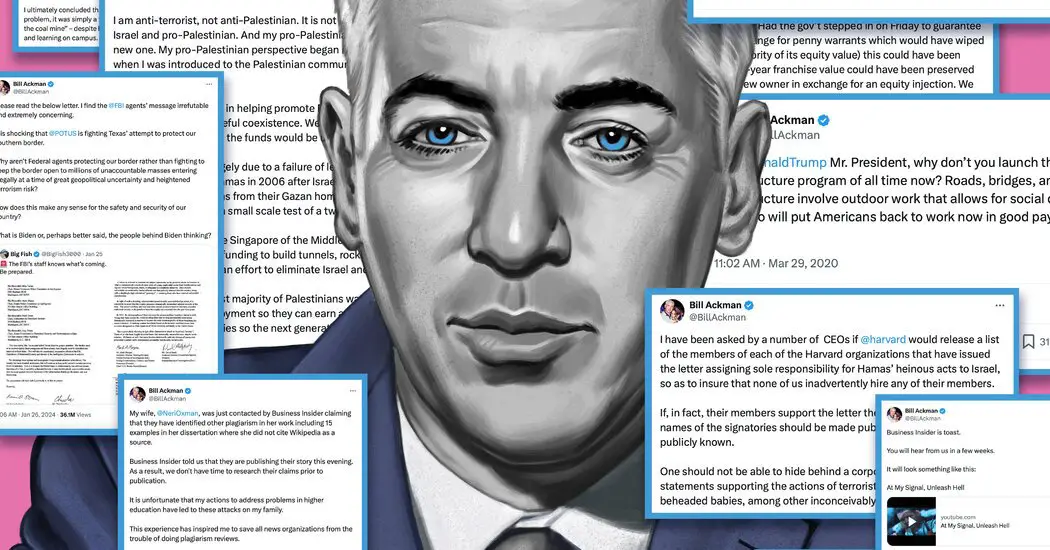

Last year, he used his account to wage an aggressive public campaign similar to those he’s used against chief executives of major companies, pushing out Claudine Gay, the president of Harvard University, over her response to complaints of antisemitism, as well as allegations of plagiarism. He pivoted from that fight into one about diversity, equity and inclusion, while questioning whether Dr. Gay was hired because of her race, a charge that drew accusations he was racist and a bully.

Ben Eidelson, a professor at Harvard Law School, called him an “interloper” and said in December to The New York Times that “We can’t function as a university if we’re answerable to random rich guys and the mobs they mobilize on Twitter.”

For some, the intensity of Mr. Ackman’s focus on the issue seemed to come out of the blue, but in fact this kind of crusade was an extreme version of what he has long done in his professional life: full speed ahead, without any regard for the kind of potential collateral damage that some say he inflicted on Harvard’s community.

Now, he’s going after reporters and executives at Business Insider and its parent company, Axel Springer, after they published articles asserting that Dr. Oxman had committed plagiarism in her academic work.

It’s a moment of intense fame for Mr. Ackman. A late February cover of New York Magazine featured a close-up of his face with the headline “Raging Bill.” He now has dozens of impersonators on Facebook and other social media outlets pretending to offer up stock tips.

And despite the uncomfortable scrutiny that has resulted for his wife, Mr. Ackman seems to be enjoying his moment in the sun.

“We live in a world in which people are afraid to speak the truth,” Mr. Ackman said. “I’ve gotten calls from some of the most prominent people in the world who say, ‘I wish I could say what you’re saying.’”

So, now that he’s famous-famous, not just finance famous, what does Mr. Ackman want to do with that influence?

“I have no plans to run for president, but I do like having an independent voice and having influence,” he said. (He said he would get permission from his family members before a run for office and doesn’t expect they would give it.)

In January, he told CNBC he planned to fund what he calls a “think-and-do-tank” to come up with solutions to problems, including antisemitism and child sex trafficking, and carry them out. He said he has engaged a search firm to find the right person to direct the organization.

And in early February, Mr. Ackman announced a plan that would help him capitalize on his following: He said he would seek to raise $10 billion or more in an initial public offering from U.S. retail investors to invest in public companies — in other words, from the ordinary person who might know him from Twitter and want to buy into the Ackman brand.

The fund would operate as a closed-end fund, meaning investors could take money out only if someone else put new money in. (In a traditional mutual fund, you can remove money at any time.) In a regulatory filing, Pershing Square — whose hedge-fund clients have mostly been large institutions — said Mr. Ackman’s “brand-name profile and broad retail following” would drive investor interest, and suggested that it could become the largest closed-end fund. Mr. Ackman compared his ambitions for his closed-end fund to what Warren Buffett had accomplished with Berkshire Hathaway.

But more broadly, it might just be that what Mr. Ackman wants to do now is exactly what he’s been doing for years: telling people why he’s very right, despite a few high-profile instances where he’s gotten things very wrong in his business dealings.

“I would be a very happy man in life if I could be as certain of just one thing as he is certain about everything,” Mr. Icahn said of him in an interview.

.

‘I Like to Fix Things That Are Broken’

Mr. Ackman is quick to exert his influence on everything from the personal lives of the people around him to corporations to world events.

“I like to fix things that are broken,” Mr. Ackman said.

Take the case of David Sabatini, a former Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and researcher who stepped down from his role at the university in 2022 after a review by other professors recommended revoking his tenure. M.I.T.’s president at the time, L. Rafael Reif, said in a letter to faculty that its own review concluded that Mr. Sabatini “behaved in ways incompatible with the responsibilities of faculty membership,” for having “engaged in a sexual relationship with a person over whom he held a career-influencing role” without disclosure. It had also received reports of “unprofessional behavior” by Mr. Sabatini toward “some lab members.”

Mr. Ackman, who said he conducted his own review, believes Mr. Sabatini was not fairly treated.

In February 2023, Mr. Ackman said he and an anonymous donor would give Mr. Sabatini $25 million over five years to fund a new research lab. Mr. Ackman said Mr. Sabatini would open a new lab in Boston soon. Mr. Sabatini, who landed a post at a Czech university last year, wrote in an email to The Times that he was grateful for the funding.

Closer to home, Mr. Ackman also intervened in accusations of sexual misconduct. In 2010, his personal trainer was jailed at Rikers Island on a rape charge. He called Mr. Ackman, who helped him post roughly $200,000 for bail, helped him find criminal lawyers and paid his legal bills. The case never moved past a New York grand jury, though the alleged victim, who said through a lawyer that she didn’t know about Mr. Ackman’s involvement, recently filed a suit against the trainer in court using the Adult Survivors Act. (The filing said that two other women had reported the trainer to the New York Police Department, accusing him of sexual assaults. The defendant filed his own defamation lawsuit in response.)

Mr. Ackman said he’s been a longtime supporter of the Innocence Project and has paid legal bills for people he didn’t know. In this case, he said, he believes his personal trainer was unfairly accused in all three instances.

The trainer had an image of Mr. Ackman, taken from a Fortune Magazine story, tattooed on his calf as a way of expressing his gratitude and admiration.

At Pershing Square, his investment firm, Mr. Ackman also tends to get closely involved in the lives of its several dozen employees. He can be generous, personally paying for medical bills and helping employees pay off debt.

But, according to people in the organization who asked not to be identified for fear of losing their jobs, Mr. Ackman has at times taken things too far. He often critiques men’s appearances, by pushing them to lose weight and use his nutritionist. (Mr. Ackman said he had done that only with his close friends who happen to work with him.) He encourages his employees to work out at the company gym and told one of his executive assistants that the women in the office should consult him on hair and makeup decisions.

Mr. Ackman said that if he had ever said something about hair and makeup decisions, he was joking and said he didn’t remember doing so.

(He also wants to control his press narrative, warning this reporter “not to be the bad version of The New York Times.”)

He has told people, including employees, that he had a knack for setting people up with their future spouses. Roughly a decade ago, when he was still married to his first wife, Mr. Ackman hosted several of what he called singles parties at his Upper West Side apartment. He asked guests to bring their best single friend. Attendees were handed a card from a card deck and asked to find the person with the same card. “It’s a patented method,” he joked. He said he’s set up four currently married couples and dozens of people in relationships.

Big Wins, Big Losses

Control has been a professional theme for Mr. Ackman, too. He became a billionaire by following the corporate raider model pioneered in the 1980s by Mr. Icahn, Nelson Peltz, and others, in which investors take stakes in companies and demand change.

Mr. Ackman has long been fascinated by the levers of society that propel people into power. As an undergraduate at Harvard, he wrote a thesis titled, “Scaling the Ivy Wall: The Jewish and Asian American Experience in Harvard Admissions.” In it, he noted that college, and particularly a Harvard education, essentially determined “who is going to manage society.”

In late 1992, at age 26, Mr. Ackman and a classmate started his first hedge fund, Gotham Partners, straight out of Harvard Business School. He raised $3.1 million overall — from Marty Peretz, the owner of The New Republic who had been his college professor and mentor; by cold-calling more than 100 members of the Forbes 400 list (four invested, he said); and eventually his own father.

Mr. Ackman’s only serious job had been working for his father, a New York City commercial real estate broker, for two years between undergraduate and business school. “I was never good at working for other people,” he said. Even at that untested stage of his career, he felt he had his own superior approach, which he modeled after Mr. Buffett’s writings and investing strategy.

Gotham Partners quickly chalked up media attention, mostly from an unsuccessful bid with partners to buy Rockefeller Center. But one investment would feed his unyielding confidence in his convictions.

In 2002, Mr. Ackman started telling credit ratings agencies, government regulators, investors and anyone who would listen that MBIA, the world’s largest bond insurer, had understated its potential losses and had not taken adequate reserves. Because of that it didn’t deserve its pristine credit rating, he argued.

He publicly trashed the company while wagering that the stock would fall. Eliot Spitzer, the New York attorney general at the time, began an investigation into whether Mr. Ackman was engaged in market manipulation.

It took nearly six years (during which time he’d shuttered Gotham Partners and started Pershing Square) but by late 2007, it became clear that Mr. Ackman had prevailed. MBIA inked settlements for civil fraud charges with regulators and paid large fines. He generated more than $1.1 billion in profits on his short bet.

Thus was born Mr. Ackman’s nearly fanatical belief that he can see, and fix, what even those closest to a situation are blind to.

He entered a period of stellar returns — some of the best on Wall Street — during the financial crash. He began to live more like a billionaire. The company bought a private jet. People close to him said he hired a stylist around this time, though Mr. Ackman said he simply had someone bring in fabrics and recommendations for business suits (“I have my own style,” he said). The not-stylist introduced him to his personal trainer.

As he ramped up his public profile, Mr. Ackman became even more vocal in the press about his investments and his plans to change companies.

Yet several bets, beginning in 2011, became high-profile disasters, including those on the retailer J.C. Penney Company and the pharmaceutical company Valeant.

At J.C. Penney, Mr. Ackman pushed hard for the company to change its strategy, away from lower-priced merchandise and toward higher-end brands. He boasted that the changes would make it one of the most important retailers in the United States, and handpicked a senior Apple executive as its chief executive. The pivot nearly ruined the company.

As Valeant and its chief executive, Michael Pearson, were being accused of buying drugs and marking up their prices, Mr. Ackman continued to praise Mr. Pearson, calling him “one of the most shareholder-oriented C.E.O.s I know.” Mr. Ackman said he wasn’t aware at the time how aggressively Valeant was marking up prices. He sold his stake in 2017 and lost $4 billion on the trade. Later that year, Pershing Square agreed to pay $193.75 million to settle claims by plaintiffs’ firms that the firm illegally traded on plans — which never materialized — for Valeant to take over its rival Allergan with insider information. (The S.E.C. earlier had dismissed allegations of wrongdoing by Pershing Square.)

Then there was Herbalife, the nutritional supplement company that Mr. Ackman said was preying on people as a multilevel marketing scheme. “This is a criminal enterprise,” Mr. Ackman said in 2014. He said he would take the fight “to the ends of the earth” and hosted meetings, conducted research and constantly called on regulators to shut it down. And although Herbalife was eventually forced by the Federal Trade Commission to pay $200 million to consumers hurt by its practices and make changes to its business, this time, unlike with MBIA, Mr. Ackman didn’t reap the benefits. By 2018, Mr. Ackman sold his entire position in the company and lost roughly $1 billion.

Still, he had access to permanent capital: a pot of money that was relatively stable.

Hedge fund managers and their teams typically spend months each year fund-raising from big pension funds and other large investors. If things go south, these investors can generally pull money out on a quarterly basis, and drain a hedge fund of its capital relatively quickly.

But in 2014 Mr. Ackman raised money on the Amsterdam stock exchange, where the rules of the exchange allowed him to create a fund where investors could get their money out only if someone else bought their stake, similar to what he plans to do with his new retail fund.

Investors had to bet long on Mr. Ackman’s correctness, as he himself has always been happy to do.

“My financial independence contributes to my ability to say what I think,” he said during the heat of his Harvard campaign. “I’m not afraid of losing my job.”

Obsessed With Harvard

Mr. Ackman has long been politically active, mostly donating to Democratic causes. More recently, he’s taken some unusual turns from that stance, at one point donating to Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign for president.

Mr. Ackman said that, though he’s a registered Democrat in order to vote in local elections, he’s “never been a party-line person,” and prefers to identify as a centrist. He said that Mr. Kennedy had raised important questions about the safety of vaccines. (He also donated to the campaign of Dean Phillips, a Democratic primary challenger to Mr. Biden, as well as to Republican primary entrants Chris Christie, Nikki Haley, Vivek Ramaswamy and Doug Burgum.)

During the pandemic, Mr. Ackman started to opine more on current events, urging then-President Trump to “launch the biggest infrastructure program of all time now” in late March 2020, and pushing him to “graciously” concede the 2020 election.

Last March, he hosted a small dinner at his Manhattan penthouse apartment and asked the dozen or so guests to bring ideas for ending the war in Ukraine. That was one world crisis that he wanted to fix, but by the time the entrees were served, another one required his attention: Silicon Valley Bank had started to unravel suddenly.

Mr. Ackman said he asked Jamie Dimon, who was in attendance, whether he would consider buying the bank. (JPMorgan Chase didn’t, though it did buy First Republic bank a few weeks later.) Mr. Ackman spent the rest of the weekend making calls to powerful people and posting about how he could help save the banking system.

Still, only since October has he engaged in campaigns on social issues that resemble the intensity of his corporate activist campaigns.

In the fall, the 12 members of the governing board of Harvard University learned what so many chief executives and corporate boards have over the past few decades: Once Mr. Ackman gets fixated on an idea to change things, he won’t stop.

Shortly after the Hamas attacks on Israel, Mr. Ackman became a vocal critic of the response by Harvard president Claudine Gay to complaints of antisemitism on campus. He quickly began to attack her by saying she had been hired because of her race and gender; from there, he used the occasion to join a larger crusade against diversity, equity and inclusion efforts at universities and in workplaces.

“Her identity made people feel more comfortable attacking or scrutinizing in a way they wouldn’t have in the past,” said Julie Park, a professor of education at the University of Maryland at College Park and the author of “Race on Campus: Debunking Myths With Data.” “If Claudine Gay had been your traditional old white man, would he have gone after her in the same way?”

After a stream of critical posts about Dr. Gay and calls, texts and letters to her and members of Harvard’s governing board, he started calling for her ouster in December after she testified before Congress and appeared to evade questions about whether students should be disciplined if they called for the genocide of Jews.

Mr. Ackman then amplified reporting that seemed to show Dr. Gay hadn’t properly cited other researchers in her academic work, adding plagiarism to the list of charges he made against the Harvard president. He called Harvard’s response to the accusations “a scandal and a stain on the reputation of Harvard that goes far beyond President Gay,” in a series of lengthy posts on the subject.

On Jan. 2, Dr. Gay resigned. In her letter to the Harvard community, she wrote that it was “frightening to be subjected to personal attacks and threats fueled by racial animus.”

Mr. Ackman said his calls for her ouster were not motivated by racism. He pointed out that he also called, though with less intense focus, for the resignation of presidents of M.I.T. and University of Pennsylvania, who also testified in Congress, and are both white women. He said he wanted to intervene because “the Harvard I love has lost its way.”

He remains critical of D.E.I. initiatives at universities, and said on X that “racism against white people” is “deemed acceptable racism.”

“Since October 7th, yes, I do feel like I’ve been in a war,” he said in a February interview with a podcaster, Lex Fridman.

Mr. Ackman has said publicly that he’s gotten calls, handwritten letters and emails thanking him for his Harvard campaign. Brent Saunders, chief executive of Bausch & Lomb, who was once on the other side of Mr. Ackman on an activist campaign, said he sent Mr. Ackman a note to thank him “for bringing this issue to the forefront for many people,” referring to antisemitism.

Still, at least three advisers to his Pershing Square Foundation have resigned because of Mr. Ackman’s support for David Sabatini and his campaign against Dr. Gay.

Joshua Sanes, a neuroscience professor at Harvard, resigned from an advisory panel after Mr. Ackman called for Dr. Gay’s ouster.

“He’s using his wealth to bully the university to change their politics in accordance with his political agenda,” Mr. Sanes said.

Mr. Ackman said he never used his money or threatened to withhold or withdraw donations to Harvard to influence events there. “The only thing I used is my Twitter account and my ability to write,” he said.

It was, he said, his relatively newfound concerns over antisemitism that have motivated him to push for changes in society. And he has found himself increasingly interested in Israeli politics.

This month, he and Dr. Oxman hosted a dinner at his apartment for a few dozen friends where Yuval Noah Harari, the Israeli intellectual and best-selling author of “Sapiens,” spoke. Mr. Hariri raised concerns about the radical, far-right faction within Israel that is seeking to push out Palestinians from the country. (Mr. Ackman said in an interview that he shares those concerns.)

For decades, Mr. Ackman had been involved in Israeli causes, and has given money to both Israeli and Palestinian organizations. But Mr. Ackman’s father, who died last year, had pushed Mr. Ackman to do more to fight antisemitism, he said.

Still, before Oct. 7, Mr. Ackman was often skeptical that antisemitism was a major issue and told his father as much. The response at Harvard in particular after the Hamas attacks caused him to change his mind.

Defending His Wife Against Plagiarism Accusations

In 2017, Mr. Peretz was one of two people to help set Mr. Ackman up with Dr. Oxman, then a 41-year-old professor at M.I.T.’s Media Lab.

Born in Israel, Dr. Oxman came to M.I.T. in 2005 as a graduate student at the Media Lab, where she studied design computation and worked on she calls “material ecology.” According to former colleagues, Dr. Oxman’s recognition inside and outside her department quickly eclipsed that of other students and even professors.

She became an academic celebrity, and even the subject of a New York Times profile that highlighted her friendship with the actor Brad Pitt, a design hound. (Mr. Ackman told Mr. Fridman on his podcast this year that he had been momentarily worried that “Brad Pitt’s going to take my girlfriend.”)

Dr. Oxman, who earned a spot on the faculty after finishing her degree, left M.I.T. several years ago and started her own research, invention and design firm, OXMAN. (She declined to comment.)

Three days after Dr. Gay resigned from Harvard over the plagiarism accusations, Mr. Ackman began to post on X that Business Insider would shortly publish a story that accused his wife of plagiarism. The publication reported that she had quoted Wikipedia in 15 places, without citation, in her 2010 thesis.

He continued to post lengthy diatribes over the next days and weeks, drawing more attention to the accusations against his wife. He also seemed to take a very different position on plagiarism when it came to the questions about Dr. Oxman’s work than he had on Dr. Gay’s work.

He defended Dr. Oxman in a slew of lengthy posts on X and other forums, arguing that M.I.T.’s faculty handbook didn’t explicitly mention Wikipedia until 2014, and noting that there were issues in only four paragraphs out of 2,700. It was “clearly not theft of intellectual property,” he said on CNBC.

Since then, Mr. Ackman has called for the firing of the Business Insider reporters who wrote the article and asked the publication for a retraction. He’s threatened to sue and retained the aggressive defamation law firm Clare Locke, the same firm that Harvard engaged to go after the New York Post for accusing Dr. Gay of plagiarism. Through his lawyers, he asked the company to publicly apologize and create a fund to “compensate other victims of Business Insider’s libelous reporting and to discourage their inappropriate conduct in the future.” (Business Insider stands by its article.)

Mr. Ackman also said he planned to conduct plagiarism reviews on the work of all professors from M.I.T., including the president. The review is ongoing, a spokesperson for Mr. Ackman said.

But Mr. Ackman told the podcast host Mr. Fridman in an interview that he has been advising his wife that it could be good for her in the long run. “You’re mostly known in the design world. Now everyone in the universe has heard of Neri Oxman,” Mr. Ackman said.

“You’re going to be doing an event in six months,” he continued, recounting the rest of his pep talk. “It’s going to be like the iPhone launch, because everyone’s going to be paying attention and they’re going to want to see your work.”

Now, as he creates his new fund, more eyes are on Mr. Ackman.

On X, he’s offered hints of where his social preoccupations might turn next, with an increasing number of posts criticizing President Biden’s positions on immigration, relating it to crime around the United States.

But Mr. Ackman declined to talk about where he would focus his intellectual energy in the near future. He’s still agitated by what he sees as the media’s power “to destroy lives” — not only at Business Insider but more broadly.

Would he ever buy his own publication?

No, he said. “Thanks for playing! Next!”