Armed with a three-and-a-half-foot-long bamboo stick with a slit cut on one end, a 14-inch World War II Japanese bayonet, and a silenced .38 Special revolver pistol, Nicholas “Nick” Sanza was deep underground in the Viet Cong tunnel system. He was wearing the same black pajamas of his enemy, strictly ate their food, and used their skills to hear in the dark what his eyes could not see.

“I was a tunnel rat. Some of the tunnels I went down were close to 60 feet down,” Sanza told Task & Purpose.

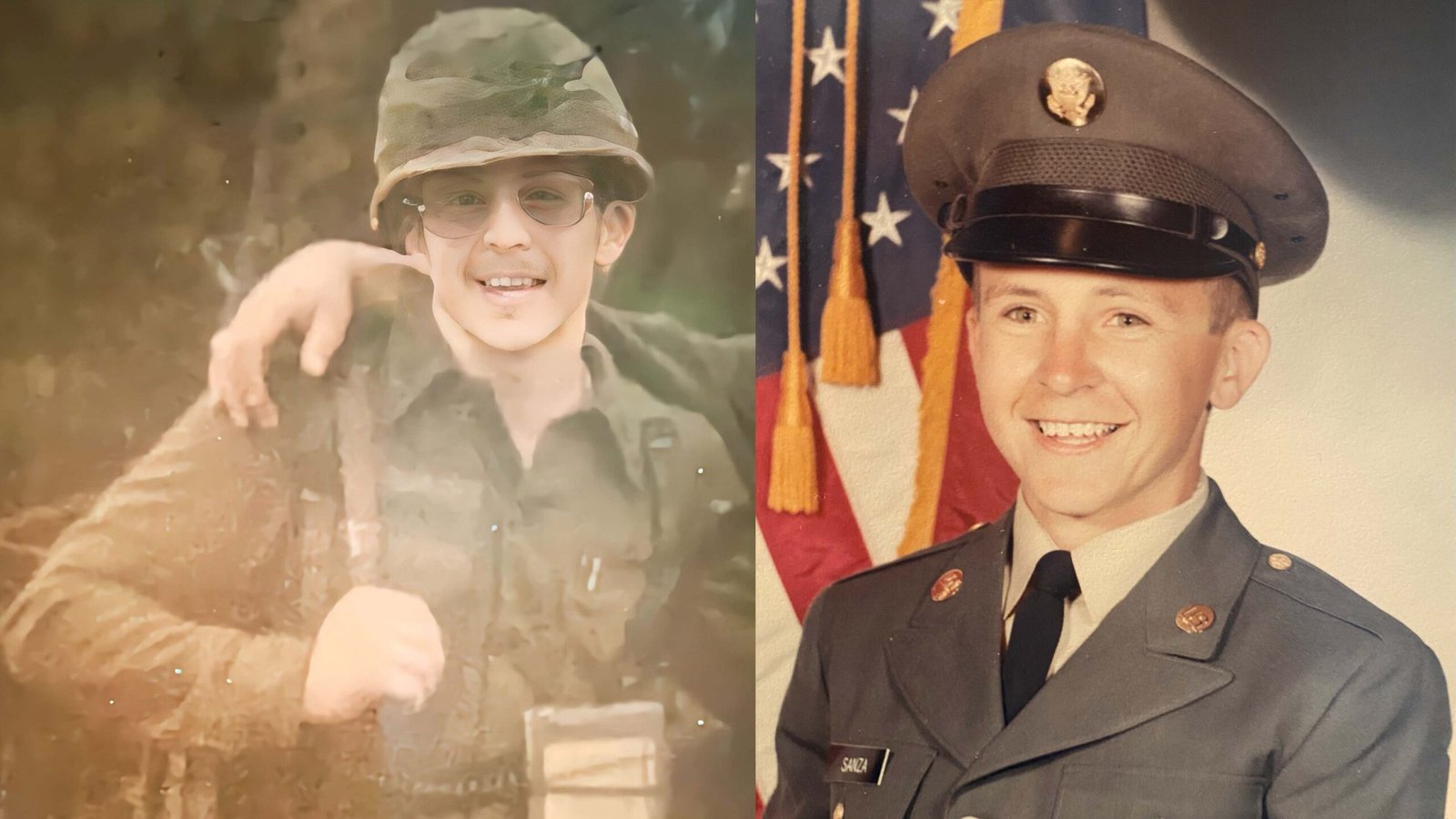

Sanza joined the Army after high school, carrying on a family military tradition. His grandfather William Kramer, Sanza says, served in President Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War, and his father was Gen. George S. Patton’s last driver during World War II. Sanza’s son also eventually joined the Army, serving as a sniper in Iraq and Afghanistan.

An underground war

Early in the war, U.S. troops had discovered a tunnel system that ran 125 miles. What came to be known as the Cu Chi tunnels twisted and turned to dampen explosions, disguised ventilation holes and went three levels deep. A massive assault by 30,000 U.S. troops in 1967, known as Operation Cedar Falls in 1967, tried to root the tunnels out. But tunnels the Americans missed in Cedar Falls were used to launch the 1968 Tet Offensive.

By 1970, B-52s were dropping delayed-fuse bombs onto tunnel complexes. The bombs would penetrate deep underground before exploding.

Sanza enlisted in 1971. Initially trained as a cryptographer, he was pulled out of that duty directly from graduation into tunnel rat duty. But while many tunnel rats were attached to units with a mission to find and destroy them, Sanza was gi war dragged into its final years: find any Americans killed or left in the tunnels.

Carved into jungle floors, the tunnels were small enough that an average-sized American would have trouble fitting into them. But guys like Sanza, at 5-foot-4 inches tall and 130 pounds, could fit.

Sanza was first trained by a Defense Intelligence Agency warrant officer who had built tunnels in the Philippines during World War II. His training was a master class in how to survive in the pitch dark of tight underground tunnels. He learned quickly and kept adding to his knowledge once in Vietnam. He learned not to go into tunnels that were wet, a sign that the Viet Cong would flood the tunnel to kill any would-be invaders.

“I was taught to hear with my eyes and see with my ears, which is real,” Sanza said during the podcast. “You go in that tunnel, it’s dark. You gotta see with your ears. If you can’t hear anything, it goes back and forth.”

Sanza says he developed a bamboo stick with a slit on the end so he could disable wire traps or move poisonous snakes and scorpions. He used a Japanese bayonet for hand-to-hand fights to keep enemy soldiers from alerting their comrades in the tunnels.

“They saved my life many times. If it wasn’t for my designed weapons, the tunnels would have been my grave,” Sanza told Task & Purpose. “These two weapons kept me alive.”

He used the Viet Cong approach to remain out of sight, out of mind. Sanza wouldn’t shower for many weeks, cover himself in mud and leaves, stuck to a Vietnamese diet, and wore the Viet Cong black pajamas. This allowed him to be deadly silent, and not be betrayed via scents that were unique to Americans.

A search for POWs

While earlier tunnel rats had been sent underground to explore and destroy the tunnels, Sanza was assigned to missions with a specific goal. As the war reached its later stages, U.S. intelligence believed American POWs might be held in tunnel systems and sent tunnel rats like Sanza to find out.

His first mission came on the Laos-Cambodia border in 1972. Sanza recalled how he had a list of 1,200 Missing In Action (MIA) American service members’ names at the time. He found two dead Americans in the system.

“So when I went down there, you know, the first time I went down, there was two guys. Actually, there were three, but there’s two guys in the tunnel. They had stuffed our POWs [in the tunnels],” Sanza said during the podcast.

Shocked and angry by the find, Sanza said he demanded the DIA agents running the operation tell him the full scope of the mission. He also asked what happened to other tunnel rats that had come before him.

“How many guys made it?” he asked. “He said, ‘None. You’re last of the four.’ I said, ‘what happened to the three? [He said,] ‘They died the second day.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Oh, God, thanks for telling me that,’” Sanza said. “But I don’t get scared. Fear is what teaches you what’s going to happen. Scare teaches you that you’re going to die because you’re going to run scared out of there, you’re going to be crying, you’re going to get out of there. You’re done.”

Sanza worked through the final days of the War, finding the remains of 30 Americans before the U.S. withdrew from the area. According to the Defense POW/MIA Agency, 1,573 Americans are still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War.

Today, Sanza tells his story at public events, but struggles with PTSD from his time in the service. He spoke with Task & Purpose about his time as tunnel rat, and sent pictures and documents from his service. But he eventually came to believe discussing his service was damaging to his mental state and ended the interviews.

But he remains proud of his service and particularly his missions to find POWs and the remains of Americans he recovered.

“Everyone that I found there was dead, and that’s through all the tunnels that I went through,” Sanza said. “It’s something you don’t forget, you know. And it’s something I still don’t forget, but you deal with it.”