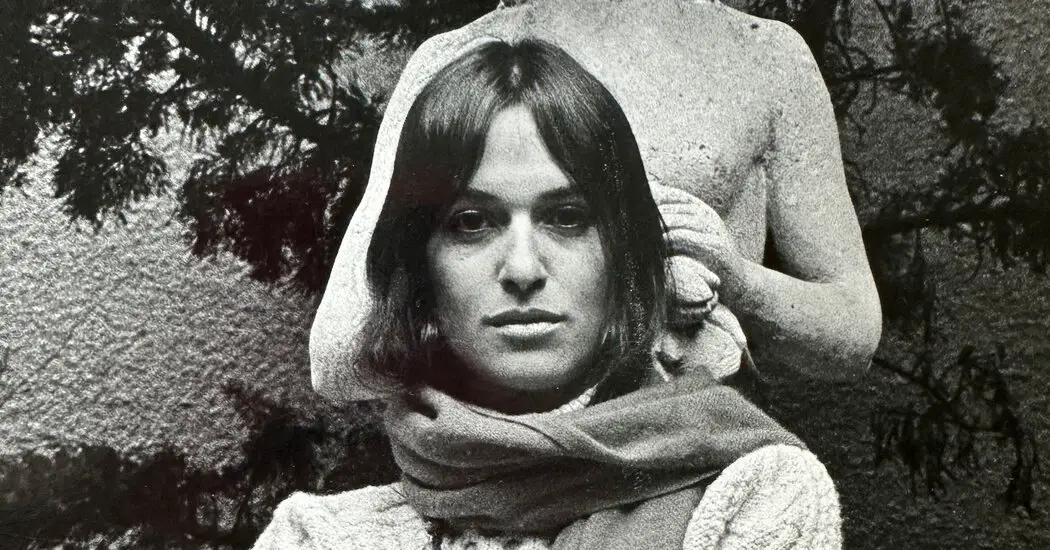

Kate Coleman, an iconoclastic Bay Area journalist who began her career as a left-wing radical, writing about the patriarchy, politics and polyamory, then made enemies among her erstwhile comrades when her reporting cast a harsh light on the Black Panthers and the environmental movement, died on Tuesday in Oakland, Calif. She was 81.

Carol Pogash, a close friend, said her death, in a memory-care facility, was caused by complications of dementia.

For decades Ms. Coleman operated at the center of a fervid community of journalists and activists in and around Berkeley. Like her, most of them had attended the University of California in the 1960s, helping to define the campus as a hotbed of political and social activism.

Her subsequent writing career, most of it as a freelancer for anti-establishment publications like Ramparts and The Berkeley Barb as well as national outlets like Newsweek and The Los Angeles Times, tracked the transit of the American left through its many phases, from early idealism through violent extremism to late-stage disenchantment.

Like Eve Babitz and Joan Didion, she positioned herself as a young female writer who was both immersed in the moment and able to stand outside it, casting a gimlet eye on the ironies and excesses of America’s “left coast.”

As an undergraduate at Berkeley, Ms. Coleman was an early participant in the university’s Free Speech Movement and was among the hundreds of students arrested in December 1964 for occupying Sproul Hall, a campus administration building.

After graduating in 1965, she spent three years at Newsweek, in its New York headquarters, where she was among the few young women allowed to write occasionally for the magazine. (A few years after she left, in 1968, a group of female employees successfully challenged Newsweek’s discriminatory policies.)

Ms. Coleman succeeded at Newsweek by offering something different: Where most of the staff came from buttoned-up East Coast colleges, she arrived bearing news from the free-spirited West.

“She was the resident hippie, the resident Berkeley radical, and she was proud of it,” Harriet Huber, who worked with Ms. Coleman at Newsweek, said in a phone interview.

Returning to the Bay Area, Ms. Coleman established herself as a freelance writer and radio producer. Among other gigs, she wrote a column for The Berkeley Barb, a scrappy magazine that was required reading among the region’s counterculture.

She used the column to cover a gamut of topics that occupied the minds of the young and hip in the late 1960s and early ’70s: Watergate, second-wave feminism, free love, radical politics, venereal disease.

She wrote in a casual tone, tinged with but not drenched in the hippie vernacular of the time — profanity, but not too much; a single “ain’t” in a column of otherwise Strunkian grammatical precision.

She was also willing to go further than most reporters. In 1969, Ms. Coleman was at a racetrack east of San Francisco covering the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, where members of the Hells Angels biker gang were hired as security (and where one of the bikers stabbed a man to death). While backstage waiting for the Rolling Stones to come on, she saw a biker beating a concertgoer. When she intervened, he grabbed her and slammed her repeatedly into a Volkswagen van.

For a 1971 article on prostitution for Ramparts, she not only embedded herself in a brothel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side but also turned a trick herself.

“You couldn’t be in Kate’s presence without being impressed by her brashness,” Steve Wasserman, the publisher of Heyday Books in Berkeley, said by phone. “But it would also get her in trouble with her dogmatic comrades.”

In 1977, the Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit newsroom, commissioned Ms. Coleman and another reporter, Paul Avery, to examine the unsolved murder of Betty Van Patter, a former bookkeeper for the Black Panthers.

After nine months of reporting, their 1978 article, “The Party’s Over,” published in New Times magazine, concluded that the Panther leadership, in particular Huey P. Newton, one of the party’s founders, had most likely ordered Ms. Van Patter’s killing because she was about to reveal corruption within the organization.

Ms. Coleman received death threats and went into hiding for several months. She bought a handgun and bars for her windows — then submitted them as expenses.

She made a new set of antagonists in 2005 with her book “The Secret Wars of Judi Bari: A Car Bomb, the Fight for the Redwoods, and the End of Earth First!”

Judi Bari, until her death from cancer in 1997, had been one of the most revered figures in the radical wing of the environmental movement. But in Ms. Coleman’s telling, she was a “tyrannical diva,” paranoid and obsessed with her own martyrdom.

The book drew protests from Ms. Bari’s defenders, some of whom would interrupt Ms. Coleman during stops on her book tour. At least one store canceled her appearance. “Is the Biographer of Activist Judi Bari a Tool of the Right — or Just a Skeptical Liberal?” asked a headline in The San Francisco Chronicle.

“Why not focus her energies on problems of the right?” the author of the article, Edward Guthmann, wrote.

Ms. Coleman responded: “The right has too many problems for me to even begin to start covering. I don’t want to research that. It’s not what I knew intimately. It’s what I know from afar.”

Kate Ann Coleman was born on Dec. 7, 1942, in Rutherford, N.J. Her father, Robert, was an engineer for a machine-tools company. Her mother, Lilian (Anson) Coleman, went blind after surgery when Kate was 3 and was largely confined to their home.

Ms. Coleman leaves no immediate survivors.

Kate’s parents divorced when she was 10. Soon after, she moved with her mother and her older sister, Susan, to Encino, Calif., to be near her mother’s wealthy brother.

Her political awakening came in early 1960, soon after she arrived at Berkeley. The House Committee on Un-American Activities had come to San Francisco for a field hearing into allegations of Communist subversion in the Bay Area. Hundreds showed up in protest, which ended with the police turning fire hoses on the crowd without warning.

Ms. Coleman joined Slate, a progressive campus political party, and eventually the Free Speech Movement, which was led in part by Mario Savio. She graduated in 1965 with a degree in English literature.

Her writing was not entirely political. Like most freelance journalists, she wrote whatever came her way: celebrity profiles, personal essays, restaurant reviews, even accounts of her rather active sex life, which she discussed in terms too explicit for a family newspaper.

For a time she also worked once a week as a host at Chez Panisse, the famed Berkeley restaurant founded by Alice Waters.

And she was a later-life convert to open-water swimming, mostly in the San Francisco Bay. She routinely won races in her age group, and once a year she swam from Alcatraz, in the middle of the bay, to San Francisco.

She would dive in wearing just a swimsuit. Wet suits, she said, were for wimps.