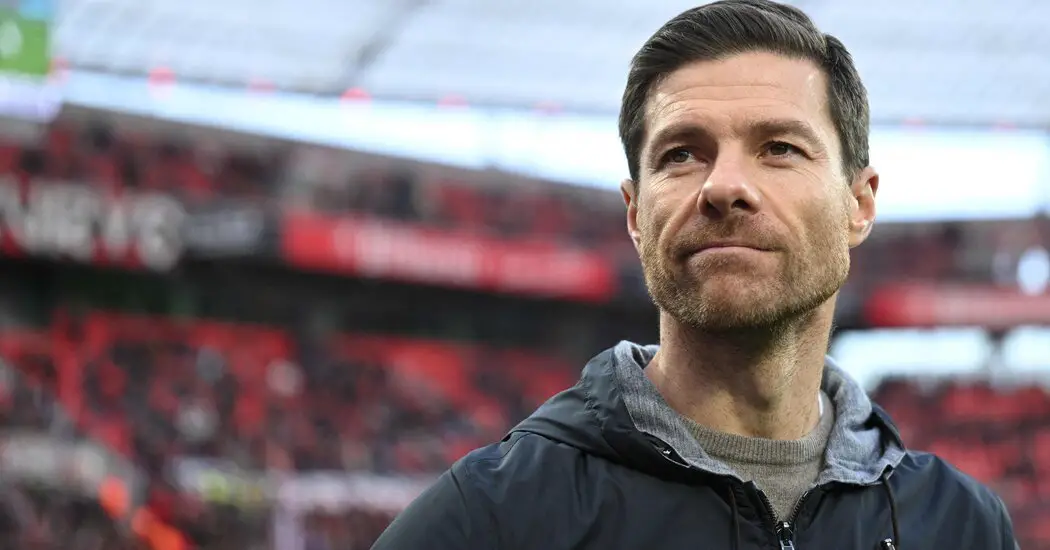

Xabi Alonso has always done things at his own speed. As a player, it was his coolness, his control, his capacity to wait until precisely the right moment that made him one of the finest midfielders of his generation. As he contemplated the idea of becoming a coach, he saw no reason to change. He would continue to treat patience as a virtue.

He did not start out on the second phase of his career with a five-year or a 10-year plan in mind. All he knew was that he was not in a rush. “I had an idea that I did not want to go too quickly,” he said. “But I had not really mapped anything out.”

There were plenty of people who were more than happy to do it for him. Everything about Alonso seemed to indicate not only that he would go into management when his playing days drew to a close, but almost that he should. He had, after all, had the perfect education. He was as near to a sure thing as it was possible to imagine.

He had played for some of the most garlanded clubs in Europe. He was one of the most decorated players of his generation, having won the Champions League with Liverpool and Real Madrid, domestic titles with Madrid and Bayern Munich, the World Cup and a couple of European Championships with Spain.

He had learned at the knee of pretty much every member of modern coaching’s pantheon: Rafael Benítez at Liverpool; José Mourinho, Carlo Ancelotti and Zinedine Zidane at Real Madrid; Pep Guardiola and Ancelotti again at Bayern Munich. (Even then, he admitted that there is one notable absence from that list: Alonso would have “loved” to have been coached by Jürgen Klopp.)

And, just as important, he had been a keen and gifted student. It was only in the last few years of his career, in Madrid and Munich, that Alonso actively sought to learn what it took to be a manager: He made a point of peppering Ancelotti’s and Guardiola’s staff members with questions, trying to arm himself with as much knowledge as possible. “I tried to be curious about the manager’s work,” he said.

He had, though, always been more cerebral than most of his peers, an avid reader off the field and an expert interpreter of the game on it, blessed with such foresight that it sometimes appeared as if he was playing in real time and everyone else was on satellite delay. His coaches, modern soccer’s most revered minds, regarded him as their brains on the field.

From the moment he retired, then, Alonso could probably have walked into any job he wanted. He could have fast-tracked his coaching qualifications, started doing a bit of judicious punditry work, called in a few favors, and been in charge of an underperforming Champions League team almost before the year was out. That, though, is not Alonso’s style.

And so, instead, he took a sabbatical, and then set about earning his spurs. He spent three years back home in San Sebastián, working in the youth academy at Real Sociedad, his first club, the one he supported, the place where his father had worked. He did not conduct a series of regular interviews to ensure people knew about all of his achievements. As far as it is possible for someone of his renown, Alonso stepped into the shadows.

Reasonably frequently, someone would try to coax him into the light: from Spain, from Germany, from England. “I had other possibilities,” he said, diplomatically, in an interview this week. “But I didn’t see them that clearly. I didn’t want to go somewhere I was not convinced.” He wanted to wait for just the right time, just the right place. A year ago, when Bayer Leverkusen approached him, he had a sense that it might have arrived.

“I had the feeling that I had taken the right steps,” he said. It felt like a risk, of course, but he was ready. “It was the moment that either I tried, or I stayed at home. Maybe that would have been an easier life. It would have been more relaxed than right now.”

Leverkusen seemed a good match, though, the sort of club where expectations are high, but not unrealistic, and the pressure intense, rather than overbearing. It was a team with a good squad with ample room for improvement, a clear structure, a coherent vision of itself. “I had the feeling that everyone was pushing in the same direction,” he said. “That’s helpful. I had the feeling it was the right time and the right place.” He took the job.

It was at that point that Alonso’s plan to take things slowly started to fall apart. Leverkusen had been toiling at the foot of the Bundesliga when he arrived. But by the end of his first season, he had managed to steer the club back into the Europa League.

The job would soon get harder. Over the summer, Leverkusen sold Mousa Diaby, an electric French winger who had become the team’s most coveted asset. And yet, after 11 games of the new Bundesliga season, Alonso’s team has not lost a game. Leverkusen is top of the table in Germany, two points ahead of Bayern Munich. It has scored 34 goals. The only game it has not won was a 2-2 draw away at Bayern.

All of which means the 41-year-old Alonso has overseen the best start to a Bundesliga season any team has ever made, outstripping even the imperious, Guardiola-era Bayern side in which he was a central figure.

He now has to spend rather more time than he might like offering deadpan answers to questions about whether his team can lift the championship. (Predictably, he thinks it is too early to contemplate such a prospect; ask him again in April, he said).

Alonso, it turns out, seems to be exactly as good at management as everyone assumed he would be. That does not mean he has changed his approach. He is still not in a rush. The problem is that the same cannot be said of the sport. Alonso always stood out because of his patience, because he possessed what the industry lacked.

Barely a year into his senior management career, Alonso is already the favorite to replace Ancelotti at Real Madrid, and a contender to fill any vacancy that might arise at both Bayern Munich and Liverpool. “Maybe I could do all three,” Alonso said. “With Zoom.”

He was joking, of course. He has been around long enough to know that he had to clarify that his “mind is 100 percent” at Leverkusen. It is much too soon, as far as he is concerned, to discuss where he might go next. According to his timeline, he is just starting out. “I don’t like to talk about my coaching with a lot of authority,” he said. “I don’t feel I have that authority. I’m so early.”

He is young enough that he still joins in games in training — he smiled just a touch awkwardly and briefly blushed when asked if he is the best passer of the ball at the club, a physical reaction that translates roughly as “yes” — and he still cannot quite resist the lure of continually rolling a ball under his feet, caressing it, during training sessions.

The withdrawal pangs from his playing days remain. “Playing is better,” he said. “Playing is much better. I shouldn’t say it but I do miss it.” As he is watching games unfold, he said, he catches himself quite often contemplating how much more fun it would be out on the field, putting a plan into action, rather than instructing others to do it.

That is not to say he does not find management satisfying. Given his influences — in particular that great, all-conquering Spanish team and Guardiola, whom he considers a friend as much as a former manager — it is no surprise he has a clear “idea” of how he wants his team to play: a fusion of Spanish control and German intensity, all percolated through the “intuition” of his players.

“They are the most important guys,” he said. When identifying potential recruits this summer, the key characteristic was not familiarity with a particular style but “intelligence,” the ability to shift between them, to make their own decisions, solve their own problems.

“It is not about being robots,” Alonso said. “They have the knowledge to know what might happen, and then decide what is good with their qualities.”

But management, he has discovered, is built not on grand ideas but of small gestures, too, less a matter of philosophy than personal relationships. He has had to learn “how to be a leader in certain circumstances: when to push, when to be a little softer, when not to let them relax.”

Ancelotti, in particular, provided him with a clear example of how to do that, but Alonso knows he is not there yet. He is still forging into uncharted territory, for him. He needs to persuade his players to be more consistent, he said, not to drop the level they have set, not to allow their bright start to flicker and fade.

He has never done that before. He is still learning, after all. He knows that will take time. He knows, too, that he has it. Soccer might be hard-wired to ask, almost immediately, what comes next. Alonso’s start has been quicker than even he might have imagined. That has brought opportunity, but it has also brought a challenge, too. He has to figure out how he can continue to take things slow.

Simpler Times

Among the many unique and heartening features of Sweden’s elite league, the Allsvenskan — and I will have much more to say on the competition and its thrilling final title race in the coming days — it is also the only major league in Europe happy to discover what happens if you just decide not to have video assistant referees.

At the behest of its empowered fans, Sweden, and Sweden alone, has elected not to introduce V.A.R. Given the system’s performance elsewhere in Europe this year, it looks increasingly like a wise decision.

For someone now accustomed to relying on remote confirmation of any and every incident on the field, though, it makes watching a game a slightly disorientating experience. The game on Sunday was settled by a penalty, the sort that might have been pored over for several minutes in the Premier League. Instead, the referee awarded it, the crowd cheered, and Isaac Kiese Thelin stepped up to take it.

There was no second-guessing. There was no interminable delay. The decision was made, and it stood. It was the same when Elfsborg made two (from a distance, not impossible) claims for a handball in the dying moments, just before Malmo’s victory secured its latest Swedish championship. The referee waved both away, decisively; nobody had to hold their breath, to wait for V.A.R. to have its say.

It was curious to note, too, that the protests from the aggrieved players were significantly less intense than they have become in the Premier League. Some objected, of course, and some pleaded their cases, but there was a recognizable absence of the sort of rage that can only ever be rooted in impotence. It is almost as if, by granting referees absolute agency rather than robbing it from them, Sweden has increased their authority, not diminished their status.

Correspondence

This newsletter — particularly this section of this newsletter — is never afraid to duck the big issues of the day. I feel like we proved that beyond doubt with our discourse on where you can find the best ice cream, and the subsequent conversation around whether a soccer newsletter should concern itself with where you can find the best ice cream.

Liz Honore’s question, then, might look fiendishly complex — a labyrinth of obstacles and booby-traps — but with clear eyes and a strong heart, it can be confronted head on. “Do you think, given Emma Hayes’s no-nonsense coaching style,” Liz asked, “she would have kept Megan Rapinoe on her World Cup squad, given her increased focus on nonsoccer-related issues?”

In one sense, the answer to this is quite easy. Hayes does have a no-nonsense coaching style, that is true. But she has also worked with any number of players who have, admirably, taken it on themselves to bring issues close to their hearts into the public domain. So, no, I don’t think she would have disapproved of Rapinoe’s interests away from the game.

The controversial bit is this addendum, which I may regret. I do not believe Rapinoe’s form dipped because of her advocacy work. I do, though, believe that Rapinoe’s form dipped, and I believe it is possible she was included in the squad to some extent because she was, in effect, too famous to omit. Whether Hayes would have done the same in that situation, I don’t know.

Joel Dvoskin follows that up with a series of questions related to the Jim Harbaugh scandal, which I will admit right now is the sort of cheating that does not really seem like cheating to Europeans. Why wouldn’t he steal other people’s signs? Why would you have a rule about watching your opponents in advance?

Joel’s two best queries — “Is cheating only a sin if it works?” and, “If everybody is breaking a rule, why is it still a rule?” — are worth bearing in mind as we discuss the parallel he drew with soccer.

“People cheat in soccer all the time, but it seems to happen in a the context of a tacit agreement about the guard rails,” Joel wrote, correctly. “Eventually, the Premier League will find itself in as dicey a situation as faces the Big Ten today. In a sport with such intense competition, it is only a matter of time before someone decides to take ‘rules were made to be broken’ and ‘if you’re not cheating, you’re not trying’ to a previously unimaginable extreme.”

It is entirely possible that soccer has already arrived at this moment. This week, Chelsea was accused of historic financial chicanery, and Manchester City, still facing 115 charges of similar offenses from the Premier League, announced eye-watering record revenues.

Both would rather suggest that cheating is only a sin if it doesn’t work. More important, if the Premier League is unwilling or unable to punish both Chelsea and City appropriately — and the only logical sporting punishment is retrospective points deductions for the seasons in which the offenses were committed — then the league will have no choice but to ask if there is any point in having rules on spending at all.